Simon Michaux’s report on raw material shortages for the energy transition has gone viral — but it’s based on flawed assumptions, outdated data, and a misunderstanding of basic energy principles. Beyond that, Michaux openly promotes pseudoscientific ideas like perpetual motion machines and collaborates with fringe movements. This article analyzes both the scientific errors and the deeper ideological agenda behind his work.

Shockwaves from a Doomsday Claim

It started with a jarring headline and a 1,000-page report from the Geological Survey of Finland. Associate professor Simon Michaux warned that “we don’t have enough materials or minerals on the planet to support a comprehensive global transition to renewable energy technologies”. In blunt terms, Michaux claimed the clean energy transition is impossible. He tallied staggering requirements – for instance, to replace the world’s 46,423 fossil fuel power stations, Michaux argued we’d need to build 586,000 renewable power plants. His conclusions were apocalyptic: civilization would face unavoidable collapse as fossil fuels decline because green tech simply couldn’t be scaled.

The shock value of these claims was undeniable. Michaux’s report quickly went viral, amplified by doomers, climate skeptics, and even some policymakers unsettled by its grim outlook. He presented his analysis to heavyweight forums like the IMF, the UN Economic Commission for Europe, and the European Commission, lending it a sheen of credibility. Online, collapse-focused communities trumpeted Michaux’s message as proof that the “green energy revolution” was a fantasy. For many readers (including this author), the initial reaction was alarm – could it be true we’re fundamentally short of the metals needed to build EVs, batteries, and solar panels? If Michaux was right, the fight against climate change would be hopeless.

But as the dust settled, experts began to push back. A closer look revealed that Michaux’s doomsday analysis was built on flawed assumptions and a worldview tinged more by ideology than rigorous science. What follows is a journey from initial alarm to relief, as researchers and analysts dissected Michaux’s work piece by piece – ultimately debunking the myth that a lack of raw materials will derail the energy transition.

First Cracks in the Story

The first sign that something was off came from voices deeply versed in energy systems and innovation. In late 2022, Auke Hoekstra, a Dutch energy researcher and professor at Eindhoven University of Technology, took to Twitter with a viral thread aimed directly at Michaux’s claims. “Have others told you there are not enough raw materials to transition to 100% renewables? Did they say minerals are the new oil? Maybe they believed @SimonMichaux…? If so, please explain to them they were fooled, by showing them this thread,” Hoekstra wrote. In a series of detailed tweets, Hoekstra – a Program Director at Eindhoven University of Technology – systematically dismantled Michaux’s assumptions, pointing readers to data and analysis that painted a far more optimistic picture.

Around the same time, engineer and science communicator Dave Borlace released a methodical breakdown on his popular YouTube channel “Just Have a Think.” The video, Borlace explained, was dedicated to debunking the now-infamous Michaux report “which purported to prove that there weren’t enough minerals in the world to enable us to get off of fossil fuels”. It was an unusual moment in the climate discourse: a niche technical paper becoming a viral meme, then getting called out by name in an explainer video. Borlace walked viewers through Michaux’s numbers, highlighting contradictions and oversights. In one striking example, he showed that Michaux’s own data undermined his conclusion – if you removed a single extreme assumption (more on that soon), the remaining known mineral reserves were in fact sufficient to electrify global transport.

These early rebuttals set the stage. They suggested that Michaux’s analysis might be a house of cards, impressive in bulk but ready to crumble under scrutiny. To truly understand, I dug into the details and consulted the growing body of critiques from credible analysts. The deeper I looked, the more the narrative flipped: far from delivering a cold dose of realism, Michaux’s report was riddled with errors, false assumptions, and misrepresentations. As CleanTechnica analyst Michael Barnard would later put it, “Michaux makes so many compounding mistakes that it’s remarkable anyone takes him remotely seriously”.

Dismantling the Data: What Michaux Got Wrong

Why were experts so quick to challenge Michaux’s conclusions? It turns out his entire forecast of doom rests on a series of deeply flawed assumptions. As analyst Noah Smith summarized, “a closer look shows that Michaux’s assumptions are deeply flawed” – and when those assumptions are corrected, the supposed mineral “shortage” evaporates. Let’s unpack the biggest problems that experts found:

Assuming No Technological Progress

Michaux treated technologies as static – effectively freezing innovation at today’s state of the art. In reality, clean tech is a moving target. Hoekstra and others note that battery chemistry is already diversifying; future stationary storage is unlikely to rely on scarce minerals like nickel or cobalt at all. Michaux ignored emerging alternatives (like sodium-ion, iron-flow batteries, advanced recycling, etc.) and thus wildly overestimated long-term demand for certain materials. As Barnard observed, Michaux’s projections involve “rigid static modeling that defies how markets and supply chains actually work” – essentially a straight-line extrapolation with no room for human ingenuity.

Ignoring Efficiency & Recycling

One of Michaux’s most glaring oversights was downplaying the impact of efficiency gains and recycling in reducing raw material needs. For example, he assumed each new ton of steel or aluminum for clean energy must come from virgin ore. In reality, a huge and growing share comes from recycling – “one-third of global steel is already recycled”, Barnard points out. Michaux’s model simply **“discounts the role of recycling,” failing to recognize how much scrap metal will be reused instead of mined anew. Similarly, he assumed no improvement in energy efficiency. This “willful blindness to efficiency gains” inflated his energy and material demand projections far beyond what real-world trends support.

Overstated Battery Requirements

Perhaps the single biggest mistake was Michaux’s treatment of energy storage. He posited that a renewable grid would need an enormous buffer of lithium batteries – so large that it consumed most of the world’s lithium, leaving little for electric vehicles. How large? Michaux misinterpreted one study to claim that Germany alone would require 12 weeks of full backup storage (all battery-powered) to cover renewables’ variability. In fact, the study’s recommendation was 24 days, not 12 weeks, and it assumed a mix of solutions, not just lithium batteries. By concocting a scenario where lithium-ion bears the full burden of grid backup, Michaux arrived at absurd conclusions – like a €3.6 trillion price tag for German batteries that would supply “400 times the country’s actual [electricity] demand”. In reality, grids can be balanced with a portfolio of tools (transmission, demand management, diverse storage types). The world will need orders of magnitude less storage than Michaux assumed, and much of it won’t even use the vulnerable minerals he focused on.

One-for-One Replacement Fallacy

Michaux’s accounting took today’s fossil-fueled economy and essentially swapped every piece for an equivalent green piece, 1:1. This misses how systems transform. Analysts note that a fully electrified world won’t have the same infrastructure or energy usage patterns. For instance, Michaux calculated materials as if we must replace every kilometer driven by gas cars with an electric car kilometer. But new mobility models (like more mass transit, fewer cars, smarter logistics) can shrink the total vehicle fleet. RethinkX, a futurist think tank, projects an 80% reduction in cars through shared autonomous EVs – Michaux dismissed this, but then paradoxically argued that if it did happen, the remaining EVs would be driven so much their batteries wear out faster. It’s a convoluted stance that fails to imagine any upside: either we have too many cars or too few; Michaux managed to portray both as doom. What he didn’t consider is that entire sectors will disappear in a clean economy – e.g. the colossal fuel supply chain. As Nafeez Ahmed explains, an electrified transport system eliminates the need to extract, ship, and refine billions of barrels of oil and tons of coal, “freeing up vast quantities of metals from the obsolete oil, gas, coal and ICE infrastructure” that can be recycled. Michaux’s models simply never accounted for these system-wide shifts, leading him to double-count demand and ignore huge savings.

This is just a sampling of the errors identified by experts. Virtually every major calculation in the Michaux report has been rebutted in detail: his skewed energy return on investment (EROI) figures for renewables, outdated data on mineral reserves, failure to account for resource substitution (using more abundant materials when shortages loom), and so on. As Ahmed observes, “I was disappointed to find that Michaux’s new report was replete with false assumptions, outmoded generalisations and incorrect data”. Michael Barnard was even more blunt after dissecting Michaux’s work multiple times: “each time, the pattern is the same — wild extrapolations that ignore technological evolution…and an almost willful blindness to efficiency gains. It’s as if he’s committed to proving that decarbonization is impossible, no matter how many assumptions he has to warp to get there.”.

Ideology Over Science: The Worldview Behind Simon Michaux’s “Impossible” Transition

The sheer number of mistakes in Simon Michaux’s analysis raises a question: how did a professional geologist get it so wrong? Part of the answer lies in his worldview, which comes through strongly in his public talks and associations. Far from being a neutral analyst, Michaux often sounds like a man preparing for apocalypse – a perspective that seems to have biased his work toward doom and distrust of any solution.

Designing The Future’s own investigation into Michaux’s background reveals a fascination with conspiracy theories and pseudoscience that is startling for someone advising governments. In internal presentations (later made public), Michaux has declared that “the transition to renewable energy is a big hoax” and that we’re being “led around by a trick” – he claims governments will eventually admit “sorry – there was no plan” after stringing the public along. He speaks of a coming “Great Reset” orchestrated by shadowy elites, warns that global powers intend to collapse fiat currencies and even deliberately depopulate the planet to under 1 billion people. This is hardcore collapse ideology, verging into areas beloved by internet conspiracy forums.

But Michaux doesn’t stop at political conspiracies. He is also promoting his own project — an isolated “research settlement” that he presents as a space for “new science” and preparation for societal collapse. He actively pitches this idea to audiences within esoteric, New Age, degrowth, and pseudoscientific circles, portraying it as a kind of ark — an experimental base for survival and the “restart” of civilization.

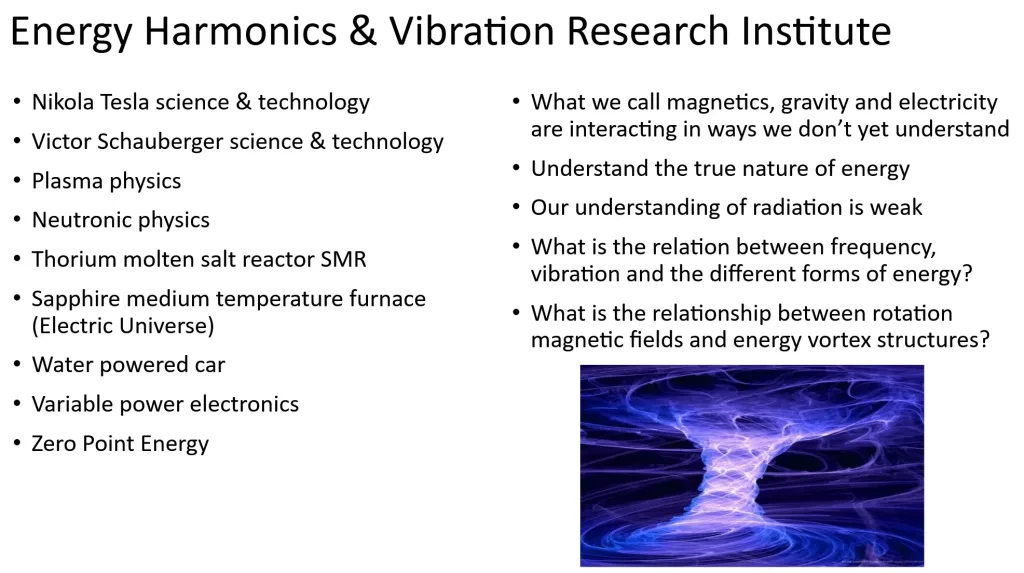

According to Michaux’s own description, his planned “Prometheus Nexus Institute” would study “Nikola Tesla’s vibration energy, energy transfer through the atmosphere, Viktor Schauberger’s vortex energy and perpetual motion machines, and Electric Universe cosmology” – in short, a grab-bag of pseudoscience.

The goal is to find the free inexhaustible energy of the ether, a phrase straight out of 19th-century quack science. He has voiced belief in “zero-point” free energy and even the idea that water-fueled cars have been suppressed by the “official science” and the ”Western World”. In the same breath, Michaux asserts that 5G and Wi-Fi wireless technology is harmful and that UFO technologies are being hidden by governments.

“I am writing a book called The New Electricity” – said Simon Michaux. And now you know exactly what kind of electricity he is talking about. “Unconventional,” as he likes to point out.

It’s a remarkable profile: a senior geologist at a national survey who espouses prepper conspiracies and magical energy theories on the side. This context explains a lot about his doomsday mineral report. Michaux approaches green technology not as an eager problem-solver but as a skeptic bordering on denialist. His analyses consistently assume nothing will improve (“fight or flight” panic mode), and he often proposes absurd alternatives instead of mainstream solutions. In fact, after claiming solar, wind, and batteries can’t work, Michaux’s preferred vision (his “Purple Transition” scenario) involves a Rube Goldberg mix of thorium reactors, synthetic fuels, and hydrogen – an inefficient mashup that one critic described as “the equivalent of someone insisting we build a fleet of steam-powered airships in the middle of the jet age.”. It seems Michaux would rather bet on exotic experiments and even pseudo-technologies than trust the exponential improvements in clean tech already underway.

Crucially, Michaux’s ideological bent aligns with certain groups who have latched onto his work. As Barnard noted, “A bunch of different groups have adopted him as their go-to guy for their particularly perverse view of the world.” These include the extreme degrowth advocates who argue the only solution is to intentionally shrink the economy, fossil fuel interests eager to cast doubt on renewables, and even hydrogen economy promoters who use Michaux to claim batteries won’t cut it. Michaux himself has openly advocated for “embracing degrowth”, essentially giving up on the idea of green growth and modern lifestyles. It’s no surprise, then, that his analysis skews negative – it was always geared to conclude “impossible”, fitting a narrative of inevitable collapse and the failure of industrial society. As one detailed rebuttal put it, Michaux’s view is “far from a sober, scientific perspective; this view is itself an ideological reaction” rooted in fear of change.

The Verdict: Transition Is Challenging But Far From Impossible

The journey from viral doom to factual debunking offers a few clear lessons. First, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence – and Michaux’s claims did not hold up when experts shone light on the details. Once scrutinized, his prediction of global mineral shortages blocking climate action turned out to be exaggerated and misleading. Yes, the sustainable transition will demand a tremendous scale-up in mining and materials processing in the coming decades. Yes, we must plan for bottlenecks, invest in recycling, and continually innovate to use less and reuse more. But nothing in peer-reviewed science or real-world data suggests an insurmountable geological barrier. On the contrary, studies from institutions like the International Energy Agency conclude that known reserves and foreseeable technology will be sufficient to achieve net-zero – with mindful policy and likely substitutions.

Second, we’ve seen how an ideological filter can twist analysis. Michaux’s collapse-oriented mindset led him to cherry-pick assumptions that confirmed his pessimism. The result was not sound science but a kind of anti-renewables pseudoscience, dressed up in technical language. As Barnard quipped, “if you thought bad takes on the energy transition were limited to fossil fuel lobbyists, Michaux is here to prove that pessimism can be just as detached from reality as corporate greenwashing.” In the end, Michaux’s work tells us less about the physical limits of Earth and more about the psychology of doomerism – a reminder that even a associate professor can build a false model of the world if they ignore human adaptability and scientific progress.

Finally, this saga highlights the importance of expert critical thinking in public discourse. Michaux’s report gained traction because it appeared exhaustive and came from an official source. It took patient explanation from people like Hoekstra, Borlace, Ahmed, and Barnard to demystify the math and reassure the public that all is not lost. Their message, backed by data, is ultimately hopeful: we are not doomed by resource scarcity. The clean tech revolution is already underway, powered by human creativity, learning curves, and yes, ample materials – if we use them wisely. The real obstacles to a sustainable future are political and organizational, not the lack of rocks in the ground.

In hindsight, the “Michaux scare” of the 2020s will likely serve as a case study in getting the energy transition story wrong. It shocked many, but it also galvanized experts to communicate more clearly about what’s possible. Today, we can say with confidence that global minerals shortages will not derail the energy transformation. The only thing that can derail it is giving up. And as we’ve seen, those urging us to abandon decarbonization – whether out of profit motive or apocalypse fervor – have a habit of being wrong. Science, innovation, and sensible planning remain firmly on the side of an achievable green future.

Sources:

Michael Barnard’s trilogy of critiques on CleanTechnica:

Simon Michaux’s Purple Delusion: The Pseudoscience of Doom

Finnish GTK Risks Credibility By Publishing Bad Minerals Study In Peer-Reviewed House Journal

How Many Things Must One Analyst Get Wrong In Order To Proclaim A Convenient Decarbonization Minerals Shortage?

Auke Hoekstra’s debunk on X;

Dave Borlace’s “Just Have a Think” video;

Nafeez Ahmed in Age of Transformation Energy transformation won’t be derailed by lack of raw materials;

Designing The Future investigations and podcast notes on Simon Michaux

The secret plans of The Venus Project organization

All other related news and articles to Simon Michaux

Read more:

Simon Michaux’s involvement in esoteric UFO circles

More on Simon Michaux’s plans

I have been at the center of all this dirrection for over 13 years and can tell you a lot of things, from detailed explanation of Jacque Fresco’s original proposals, to experience of working with the movement, to little known and insider information.

I have organized the most successful and effective team of The Venus Project movement, now represented by Designing The Future, as well as the 1.5 million subscriber Jacque Fresco channel, small and large events, radio and TV interviews, working with universities and schools, organizing events, running a network of groups in 60 cities with regular meetings, and much more. Exposed and fought fraudulent companies and initiatives to protect The Venus Project’s reputation.

Organized and negotiated the construction of The Venus Project’s smart city, with the then living Jacque Fresco, which was their best chance. This has now evolved into a full-fledged smart city project and test site for the development of the entire industry of smart cities, called “Mission on Earth”, which will be launched soon, late 2024-early 2025, and we’re directly involved.

After the new directors of The Venus Project changed course, I strongly opposed it without hesitation, especially knowing the details of the gamble – taking the side of Jacque Fresco’s original ideas. Whatever the outcomes, I will continue what I have started, with the goal of giving humanity a chance to move toward a resource-based economy, or at least to point society in the right direction. I hope you will join us.